Using GDPR Subject Access Requests to Harvest Data

| Contact Us | |

| Free Demo | |

| Chat | |

In a talk at this year's Black Hat an Oxford University student explained how he used GDPR Access Requests and a Python script to steal a slew of sensitive information on another person.

LAS VEGAS - Last year’s implementation of the Global Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) was supposed to tighten privacy regulation but an adverse effect of the legislation has resulted in vulnerabilities in the law that can be used by those desperate enough to steal sensitive information.

James Pavur, a DPhil student and Rhodes Scholar at Oxford University, walked an audience through several loopholes in the law in a talk here at the Black Hat Conference on Thursday. In the session, "GDPArrrrr: Using Privacy Laws to Steal Identities," Pavur showed how GDPR enabled him to steal a veritable treasure trove of information from an individual: his fiancé.

After obtaining her consent, Pavur fired off dozens of GDPR Access Requests, inquiries under the law that require any company to turn over data it has collected on an individual, to data protection officers at 150 companies. Pavur used his fiancé’s real name but forged other details, like creating a fake email address for her, then crafted a python script, changing a few words in each request, to contact data protection officers at the companies en masse.

“It only took me a few minutes to run but it took weeks for the companies to run research for my requests,” Pavur said.

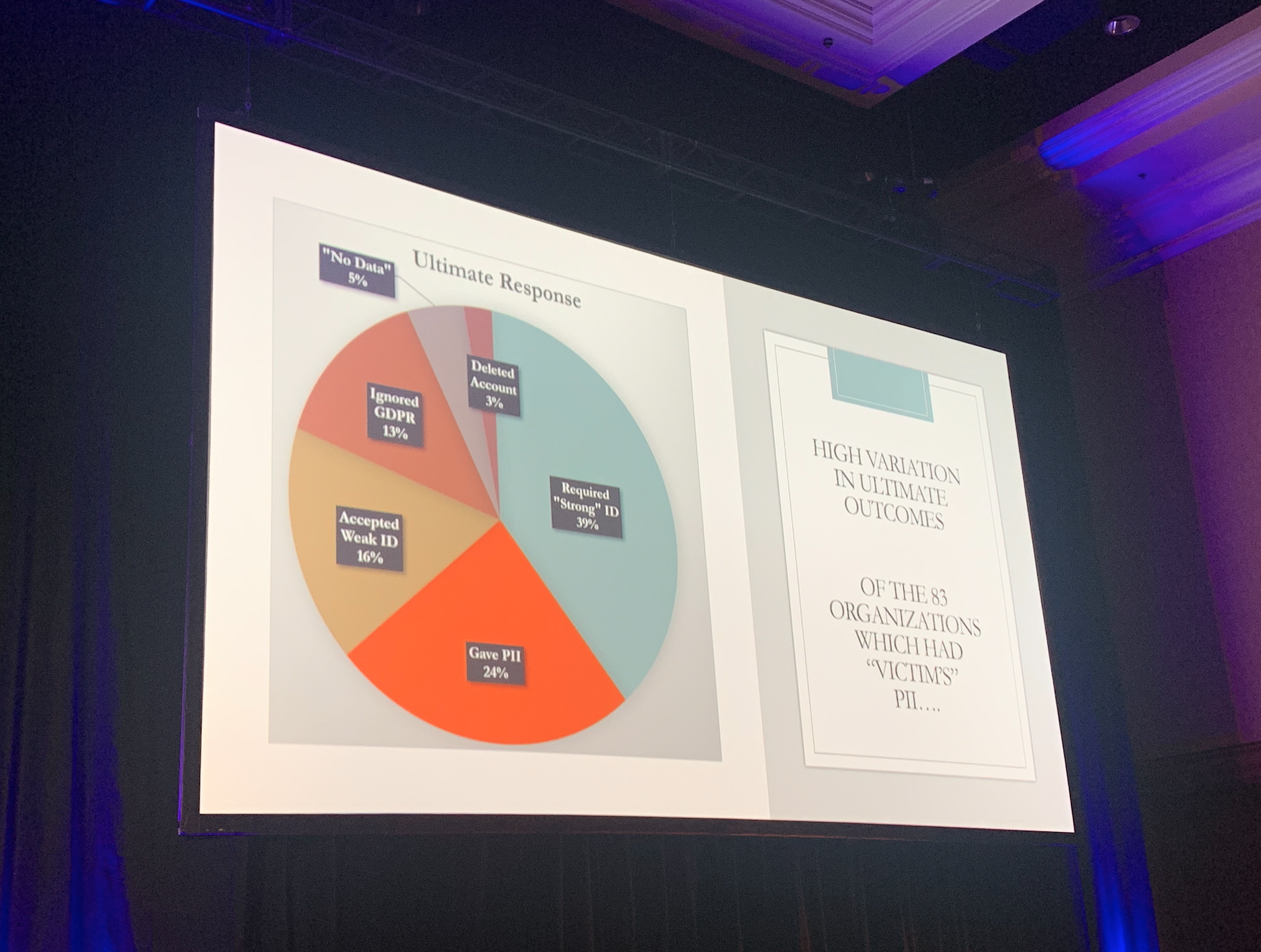

While about 72 percent of the companies he contacted, 83, got back to him, what was truly fascinating was to see the variety of responses, many which yielded sensitive data for Pavur’s phony requests.

in an attempt to confirm his fiancé’s identity, 39 percent of the responses were requests for further information that Pavur wasn’t willing to forge, data like passport numbers and such. 24 percent of the companies actually gave him the information he was seeking, sight unseen, based solely on his fake email. 16 percent of the companies wanted an additional, weaker form of identification, while 13 percent just ignored his request.

Troublingly, three percent of the companies he requested information from outright deleted his fiancé’s account after receiving the request.

“Denial of service via the GDPR was an unexpected outcome,” Pavur said.

Other companies asked for data that he was unwilling to part with; a railroad company wanted his fiancé’s actual passport but relented after Pavur said he’d send them an envelope from her residence in the mail instead.

The actual data that Pavur received ran the gamut, from social security numbers, to his fiancé’s social activity; the railroad company gave him a list of her travels, a prominent hotel company gave him data on when she stayed there, when she used the hotel’s wireless internet.

There were 10 instances where the companies sent Pavur high sensitivity data, including answers to security questions, her complete name, date of birth, and social security number. One company, an unnamed education services company with 10 million users gave him a lot of sensitive data, including his fiancé’s complete social security number.

While he wasn’t able to get her fiancé’s full credit card number, he got close, 10 digits, in addition to the card’s associated post code and expiration date.

Pavur said four things in particular about GDPR make it a ripe target for attackers. Since the law is rooted partially in fear – companies who violate GDPR can be subject to fines of four percent of its worldwide annual revenue or 20 million euros – companies often make bad decisions around how to comply with it. That fact that the law is just as ambitious as it is ambiguous tends to lead to a lot of flexible language within the law, and that there’s an actual person at the end of the line processing requests, usually someone in legal or a data protection officer, can open the company up to social engineering attacks, as well.

“The status quo in unacceptable,” Pavur said, going on to advise companies to say no to suspicious GDPR requests that could land them in a court room.

“It really shouldn’t be that kind of choice [for companies]. Rejecting GDPR requests in good faith shouldn’t come back to bite them if they were rejected in good faith,” Pavur said, adding that legislators should do all they can to reassure companies that, in addition to looking into providing some form of government-mediated identity verification service.

Pavur said that if you’re an individual, things can be a bit more bleak in regards to personal data security but that individuals should be proactive about data hygiene. If something seems fishy, look into it.

Pavur said in closing that legislators should take the experience that information security experts garner through pentesting and auditing and let it inform polices.

“Privacy laws should enhance privacy, not endanger it,” the researcher said.

Recommended Resources

All the essential information you need about DLP in one eBook.

Expert views on the challenges of today & tomorrow.

The details on our platform architecture, how it works, and your deployment options.